From Matsyendranāth to Modernity: Exploring the History, Practices, and Impact of the Nāth Yogis

नाथं गुरुं कुलदीपं गुरुं नाथं गुरुं परम्। नाथं गुरुं योगिनां च सिद्धिप्रदं नमामि तम्।।

I bow to that Nāth, who is the Guru of the lineage, the Guru of the supreme, the Guru of the Nāth Yogis, and the bestower of spiritual attainment

Nestled within the rich tapestry of Indian spirituality lies the Nātha (or Nāth) Yogi tradition that has not only stood the test of time but has also left an enduring and profound impact on India’s cultural, philosophical, and spiritual landscape. The Sanskrit word Nātha (नाथ) translates to mean “lord”, “protector”, or “master”. It possesses the dual capacity to refer to a physical lord and to indicate the specific initiatory tradition. In a similar vein, the term “Adi-Nāth” translates to “first” or “original” lord, commonly known as Śiva.

The origins of Nāth Yogis trace back to antiquity, through centuries of wisdom, discipline, and the pursuit of self-realization. This tradition, guided by nine legendary gurus, has acted as a torchbearer of ancient yoga practices and a catalyst for contemporary spiritual pursuits. Beyond the realm of yoga, Nāth Yogis have played a multifaceted role in society. They have held influential roles in politics, infused spirituality into everyday life through the concept of the householder, embraced distinctive rituals and symbolic attire, and pursued the goal of paramukti (ultimate liberation from the cycle of birth and death).

In this research paper, we explore the enigmatic world of the Nāth Yogis - their historical roots, the contributions of the nine gurus, core practices and beliefs, and the resonance of their tradition in the modern world. We look at their unique ability to harmonize the spiritual with the physical, and explore their unique influence in modern yoga.

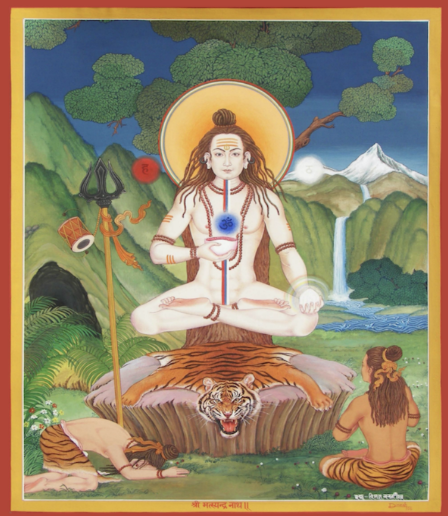

Figure 1. Unknown, Depiction of the Navnāth gurus

Historical Origins

When Lord Kṛṣṇa was on the verge of leaving his physical body, he summoned Dattatreya, embodying the divine trinity of Brahma, Vishnu, and Śiva. He expressed his deep concern for the impending Kali Yuga, a dark age defined by greed and lust, which could blind humanity to their dharma, their duty. In this foresight, he envisioned the need to guide humanity through this challenging era. Through Dattatreya, he invoked the NavNāth (nine Nāth) Gurus from the celestial realm to be reborn on Earth with the intention of guiding humanity. Lord Kṛṣṇa’s primary purpose in his incarnation was to ensure that there would be no obstacles for those who aspired to follow dharma. To safeguard his teachings, he entrusted Dattatreya with the task of formulating a tradition with the sole objective of attaining paramukti. Dattatreya established the Nāth tradition, rooted in the state of Śiva, characterized by eternal bliss and absolute detachment.

In another sacred narrative, Lord Śiva, known as Adi-Nāth, the first among the NavNātha gurus and a master of yoga, found himself resting with his beloved Parvati by the tranquil shores near their home. As both a guru and a husband, Śiva graciously agreed to Parvati’s request and began to impart the profound science and methodology of yoga. As the evening unfolded, Parvati drifted into slumber during Śiva’s discourse on yoga, threatening the teachings to be lost forever. Thankfully, due to a serendipitous turn of events, at that precise moment a fish emerged from the waters, and within its belly was a boy. The boy miraculously emerged from the belly of the fish, having soaked in the knowledge Śiva imparted, and grew to become a remarkable yogi. Śiva bestowed upon the newly emerged yogi the name “Matsyendranāth”. Matsyendranāth embarked on an extraordinary journey along the yogic path, his most devoted student being Goraknāth, who recorded this story in the Goraksha Vijaya. Generally, Matsyendranāth is regarded as the founder of the Nātha tradition and Goarkshanāth is credited with systemizing and codifying the practices. Notably, Goraknāth is commonly believed to be the reincarnation of Lord Śiva.

Ascertaining the precise moment when the Nāth Yogis were first documented poses a challenge due to the limited availability of written records from their formative years. A significant portion of this tradition’s history has been orally transmitted, and written records may have materialized many centuries later. Nevertheless, its origins are conventionally traced back to the 8th or 9th century, with the emergence of Matsyendranāth.

In this tradition, the relationship between the guru (teacher) and the shishya (student) is held as sacred. This lineage of spiritual transmission is considered the source of Nāth yoga’s sacred and esoteric teachings. It is through this lineage that the tradition has been passed down through the ages - from Matsyendranāth to modernity.

Founders & Key Figures

Within the Nāth tradition, there exist two distinct groups of revered spiritual figures: the NavNāths and the eighty-four mahasiddhas. The Sanskrit word Maha commonly means “great”, while Siddha commonly denotes “realized, perfected one”. The siddhas are considered to have attained the highest levels of spiritual realization, mastery over the self, and extraordinary powers through their dedicated spiritual practices. “The lists of siddhas vary according to time, place, and sectarian traditions, retaining, however, the number eighty-four as a symbol of completeness… in some cases siddhas in one list are considered Nāths in another”.

The list of the NavNāths, or nine lords, follow a similar pattern of variation, with a general agreement surrounding the central gurus of AdiNāth, MatsyendraNāth, and GorakshaNāth, who hold positions within the NavNāth pantheon.

AdiNāth

Śiva, in the embodiment of AdiNāth, holds the esteemed position of being the inaugural Guru to disseminate the teachings of the Nāthas. He is revered as the source of all wisdom, knowledge, and spiritual guidance, believed to transcend all attachments and limitations. While there exists a diverse array of names for the Navnāths and maha siddhis, all branches of the Nāth tradition concur that AdiNāth personifies Śiva. Many adherents also perceive Gorakshanāth as an embodiment of Śiva, with both figures occupying significant separate roles within the Navnāth pantheon.

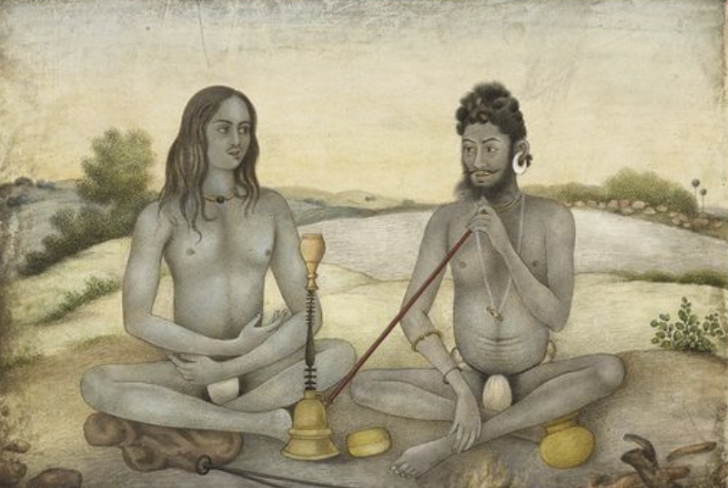

Figure 2. Dinesh Shrestha, Matsyendranāth

Matsyendranāth

Matsyendra, often referred to as the "Lord of the Fishes," is renowned for disseminating the wisdom and practices of the Nāth tradition, encompassing various facets of yoga, meditation, and self-realization. As the inaugural earthly guru of the Nath tradition, Matsyendra is credited with introducing the Kaula tantric doctrine to the world. The Matsyendrasamhita, representing his seminal teachings, occupies a distinguished position in the spiritual legacy of the Nāth tradition. His disciples, notably Gorakshanāth, are recognized for their role in organizing and disseminating these profound insights. Matsyendranāth is venerated as a master of both yoga and tantra, serving as a guiding force on the path to enlightenment.

Figure 3. Shabad Surat Sangam Ashram, Gorakshanāth

Gorakshanāth

While the Nāth Sampradaya predates Gorakṣa, its most significant expansion occurred under his guidance. Gorakṣa is often credited with initiating the ascetic Nāth yogi path, yet his teachings transcended strict asceticism. His philosophy embraced both ascetic and householder yogis, and Gorakṣa himself belonged to the latter category. A pivotal figure, Gorakshanath played a crucial role in popularizing both the physical and spiritual facets of yoga, contributing significantly to the development of Hatha Yoga traditions. His teachings underscore the importance of integrating spiritual practices into daily life, emphasizing the transformative potential of yoga for achieving not only physical well-being but also spiritual enlightenment.

Core Practices & Beliefs

The Nāth Sampradāya, akin to many Eastern traditions, provides guidelines for a harmonious existence, presenting them not as strict rules but rather as suggestions aimed at averting unnecessary troubles and suffering. It recognizes the inherent freedom and desires of individuals, advocating a life not constrained by rigid moral codes. Emphasizing the pivotal role of the mind in shaping the pleasure derived from any activity, the tradition seeks to cultivate a balanced and mindful approach to living. The overarching goal of this way of life is jivamukti - attaining freedom, peace, and liberation in the present life while also striving to break free from the cycle of rebirth, with the ultimate aim being paramukti, complete liberation. The sampradāya demonstrates that these accomplishments hinge on individual thoughts and actions rather than relying on divine intervention..

Matsyendra is credited with introducing the Kaula doctrine to the world, through the Kaulajñānanirṇaya, which imparts Kaula doctrines and reflects on the nature of the Nāth tradition. It is also a significant shift in the history of yoga, as it marks the detachment of yoga from sectarian affiliations. Subsequent Nath texts on yoga continued to embrace this trend of anti-sectarianism, and it wasn’t until the 18th-century Siddhasiddhāntapaddhati that the Nath tradition began to establish a distinct sectarian identity, and expound upon their unique siddhi practices.

Nāth practitioners have long been associated with a wide range of practices that have enabled them to attain siddhis and jīvanmukti. These practices often involve achieving immortality through yoga or alchemy, thereby mastering death itself, often personified as Yama. Nath hagiographies are replete with accounts of miraculous feats performed through their siddhis, including the ability to fly and to alleviate droughts. While contemporary Nath religious practices, both among ascetics and householders, align with mainstream Hindu devotional observances, some Nath adherents continue to engage in various tantric practices, including tantric rituals, alchemy, and yoga, reflecting the rich tapestry of their tradition's diverse spiritual pursuits.

Figure 4. Unknown, Aughar Yogi (left) & Kanphata Yogi (right)

Traditions and Lineages

Within the Nātha Sampradāya, there are twelve different distinctive initiation paths, known as panths, each representing diverse approaches and practices. While these panths provide distinct pathways, there is often overlap, allowing practitioners to incorporate elements from multiple panths into their spiritual journey. Followers of the Nātha Sampradāya are also categorized into three main stages - Avalambi, Aughar, and Kanphata. Within these separations, there is not a hierarchy, as it is recognized that many lifetimes are needed to truly progress through the manifestations of our earthly existence on our way to liberation.

Avalambi, Sathis

These are disciples and followers dedicated to studying and following Nāth traditions, striving to embody the teachings. These yogis have accepted the Guru of the Nāth lineage, and often receive instruction on the practice of yoga. These Nāthas are most in touch with the world and the manifestation of reality. In this stage especially, we see a diverse crowd of yogis, including householder yogis.

Aughar

Upon initiation, Aughars receive specific attributes of the Nātha Sampradāya, including a whistle and thread to use in ritual practice. This stage also connects the yogi with their main guru, so that they may be introduced and taught the ways of the Sampradāya in its entirety, laying the foundation for deeper spiritual engagement.

Kanphata

Kanphata is the highest initiation in this Sampradāya. During this initiation, the guru pierces the disciple’s ear, and earrings, known as kundals or darshans, are added. While there is no distinct written record of the benefit of kundals, some say that they are associated with two energy channels that help the yogi direct their sexual energy to the sahasrara cakra.

This intricate tapestry of spiritual stages and practices emphasize the diversity and acceptance within this tradition, as well as the profound layers and nature of the Nātha Sampradāya.

Figure 5. Himachal Pradesh, A Nath Yogi

Distinctive Elements within the Nāth Tradition

The Nātha Sampradāya stands out within the broader landscape of yoga practice due to its distinctive elements, notably encapsulated in the various panths and the recognition of the three stages within the tradition. However, these features are only a part of the rich tapestry that defines Nāth Yogis. One prominent aspect of their identity is associated with unique physical markers, with nudity being a historical and symbolic practice within certain sects. Although not universal among Nāth Yogis, the practice of nudity during specific rituals symbolizes a renunciation of material possessions and the external world.

Additionally, Nāth Yogis are often identified by specific physical attributes, such as hooped earrings worn through the cartilage of both ears, resulting in the common designation of "Kānphaṭā Yogīs" or "split-eared yogis." The initiation ceremony involving ear-piercing and the addition of earrings is a crucial rite of passage in the Kanphata Panth, serving as a visible commitment to the Nātha Sampradāya. Another distinctive marker is the sīṃgī, a small horn worn around the neck, visually setting Nath Yogis apart. While the symbolism of the sīṃgī may vary, it often represents a connection to the horn traditionally associated with Lord Śiva, reinforcing the yogis' alignment with Shiva and their spiritual goals.

Beyond these physical markers, the identification of Nāth Yogis is comprehensive, encompassing their spiritual practices, adherence to specific panths, and active engagement in rituals and ceremonies. These markers serve both symbolic and practical purposes, forming a visual language that communicates their dedication, renunciation, and commitment to spiritual evolution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Nātha Yogi tradition emerges as a captivating and enduring force within the vast panorama of Indian spirituality. Rooted in the profound meaning of "lord," "protector," or "master," the term Nātha encapsulates both a physical lord and a distinctive initiatory tradition. With its roots tracing back to antiquity, the Nātha Yogi tradition has weathered the sands of time, guided by the wisdom of nine legendary gurus, symbolizing an unwavering commitment to self-realization and ancient yogic practices. The Nātha Yogi tradition stands as a testament to the harmonization of the spiritual and the physical, offering a unique perspective that resonates in the modern world. As we navigate the intricate tapestry of their tradition, we witness not only a profound connection to ancient wisdom but also a continued influence in contemporary spiritual pursuits and the ever-evolving landscape of modern yoga.

Works Cited:

Bouillier, Véronique. Monastic Wanderers : Nāth Yogī Ascetics in Modern South Asia, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/lmu/detail.action?docID=4941476

International Nath Order. “Nath Sampradaya .” International Nath Order, June 24, 2023. https://www.internationalnathorder.org/nath/.

International Nath Order. “Magick Path of Tantra .” International Nath Order, April 24, 2023. https://www.internationalnathorder.org/the-magick-path-of-tantra/.

Kiss, C., Matsyendranātha’s Compendium (Matsyendrasaṃhitā): A Critical Edition and Annotated Translation of Matsyendrasaṃhitā 1–13 and 55 with Analysis, unpubl. diss., Oxford University, 2009. https://books.google.com/books/about/Matsyendran%C4%81tha_s_Compendium_Matsyendra.html?id=n-75ZwEACAAJ

Mallison, James. “Nāth Sampradāya .” James Mallinson, August 3, 2011. https://eprints.soas.ac.uk/17972/1/Nath%20Sampradaya.FP.pdf

Matsyendranath , Sri. “Initiation System .” Yoga Sadhana of the Naths . Accessed November 10, 2023. https://www.nathas.org/tradition/initiation/.

Mohanji. The Nath Sadhana . Translated Interview. Mohanji.org, November 30, 2017. www.qawithmohanji.wordpress.com/2017/11/30/the-nath-sadhana/

Powell , Seth. “Quest for the Origins of Yoga.” Introduction to the History and Philosophy of Yoga . Lecture presented in the Introduction to the History & Philosophy of Yoga course, June 1, 2022.

Referenced:

Bouillier, Véronique. Current Research on Nāth Yogīs, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://www-cambridge-org.electra.lmu.edu/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/F47ACF5272A1F3EE03E28B5541173311/stamped-9789048552450c1_p31-54_CBO.pdf/current_research_on_nath_yogis_further_directions.pdf

Muñoz, Adrián. 2022. “Powerful Yogīs: The Successful Quest for Siddhis and Power.” Chapter. In The Power of the Nath Yogis: Yogic Charisma, Political Influence and Social Authority, edited by Daniela Bevilacqua and Eloisa Stuparich, 55–80. Amsterdam University Press. doi:10.1017/9789048552450.004.

Novetzke, Christine Lee. "Jnandev Studies, vols. I and II: Songs on Yoga: Teaching of the Maharastrian Naths; vol. III: The Conservative Vaisnava: Anonymous Songs of the Jnandev Gatha." The Journal of the American Oriental Society 120, no. 4 (2000): 638. Gale Academic OneFile (accessed November 20, 2023). https://link-gale-com.electra.lmu.edu/apps/doc/A78437028/AONE?u=loym48904&sid=bookmark-AONE&xid=1a5320aa

White, David Gordon, ed. Yoga in Practice. Princeton University Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvcm4gpf.