Buddhist Six Realms: An Exploration of Saṃsāra

Buddhist cosmology presents a profound model of consciousness and reality that seeks to explain the nature of life, death, and rebirth. At the heart of this cosmology is the concept of the six realms of saṃsāra, a framework that encapsulates the varied experiences of cyclic existence. These realms - comprising the worlds of Devagati (Gods), Asuragati (Jealous Gods), Manuṣyagati (Humans), Tiryagyonigati (Animals), Pretagati (Hungry Ghosts) and Narakagati (Hell Dwellers) - are not necessarily physical places. Rather, they represent distinct states of mind and experiences of existence shaped by one’s accumulated karmas.

The Six Realms serve as a powerful metaphorical tool, as well, illustrating the consequences of actions and the cyclic, present nature of suffering. Each realm embodies different forms of dukkha (suffering), which are fundamentally linked to the three root delusions: Avidya (ignorance), Rāga (attachment), and Dveṣa (aversion). Through this lens, the realms offer an understanding of the nature of saṃsāra, emphasizing potentials for both suffering and liberation.

In this paper, I will delve into the significance of the Six Realms by exploring different philosophical interpretations, the role of karma in rebirth, their symbolic meanings, and how the wheel of life mandala art unifies these concepts for a more comprehensive understanding. By examining these realms, we can gain deeper insights into our own inner-workings, ultimately contributing to the understanding of how the cycle of saṃsāra can be transcended through wisdom, ethical conduct, and mental discipline. Ultimately, the study of the Six Realms invites us to reflect on our own lives, offering a mindful approach to overcoming suffering and cultivating compassion and wisdom.

Essential Sanskrit Terminology

We cannot discuss the Six Realms without first introducing the essential concepts of Saṃsāra, Karma, Saṃskāra, and Vāsanā. Although numerous other key terms are relevant, these four form our foundational context.

Saṃsāra is derived from the Sanskrit word "sam", meaning "together," and the root "sṛi", meaning "to flow." Thus, the literal meaning of Saṃsāra is "flowing together." It refers to the endless cycle of existence—encompassing life, death, and rebirth. In contrast to Moksha, which signifies liberation and literally means “freedom from Saṃsāra”, Saṃsāra is said to be comprised of Dukkha (suffering), sustained by Avidya, Rāga, and Dveṣa.

Karma is a trendy Sanskrit term often misinterpreted in Western society. It has become synonymous with either positive or negative consequences, yet karma itself is neutral—it holds no inherent judgment of positivity or negativity. Karma is derived from the root word “kṛ”, which literally means “to do, to make, to perform, to accomplish”. “Strictly speaking, Karma is no more than action itself”. Where this association may have come from is the interplay between karma, saṃskāra, and vāsāna.

Saṃskāra can be understood as residual impressions left by our Karma, our actions. For instance, when you show kindness to a stranger, it leaves a positive impression that may influence their perception of you. This kindness can even have a ripple effect, inspiring them to act kindly towards others. These cumulative positive impressions are known as vāsānas, or mental habits, which shape our outlook and interactions with the world.

The goal is to cease accumulating Saṃskāras, burn off our karma, and free ourselves from all attachments, ultimately achieving Moksha. In doing so, we can attain liberation from the Six Realms of Saṃsāra.

Overview of the Six Realms of Saṃsāra

Across Buddhist traditions, there is a consensus that the realms of Devagati (Gods), Asuragati (Jealous Gods), and Manuṣyagati (Humans) are considered desirable and higher realms, characterized by greater bliss than suffering. On the other hand, the realms of Tiryagyonigati (Animals), Pretagati (Hungry Ghosts) and Narakagati (Hell Dwellers) are viewed as undesirable and lower realms, where suffering outweighs bliss. Early Buddhist texts sometimes refer to this model of consciousness and reality as five realms, combining the Deva and Asura into a shared realm. This is sometimes depicted in Buddhist art, notably in the bhavacakra, wheel of life, paintings.

Within these realms reside six enlightened Buddhas, also known as the "six sages," who symbolically guide beings through their respective journeys within the six realms. The duration of existence in any realm is indefinite, contingent upon one's karma, personal ethical conduct, and discipline.

Devagati - God Realm

The Deva realm is considered the highest realm, where beings enjoy their accumulated positive saṃskāras, guided by the Buddha Indraśākra. However, even positive saṃskāras lead to vāsānas and attachments, making enlightenment challenging in this realm. The Deva realm is characterized by ecstasy, beauty, and pleasure. A significant concept within this realm, and all the realms, that contrasts with Western religious views is the notion that these states are not eternal. This provides hope for practitioners, as they understand that both the blissful Deva state and the more distressing Preta and Naraka states are temporary. These are merely states where one resides until the associated saṃskāras are burnt off or the ethical lessons are embodied.

It's important to note that while the Deva realm may be considered a godly state, the beings here have not attained Moksha. In the Deva realm, one can enjoy all the earthly pleasures without the worries of survival. However, this realm often leads to attachment and a lack of spiritual practice, resulting in further rebirths.

Asuragati - Jealous God Realm

This realm, guided by the Buddha Vemacitra, is characterized by violence, envy, and jealousy. In some traditions, the Asura realm is considered the third realm of existence or is even associated with the lower realms. Yet, in others, we see Asura on the same level as the Devas, or just below. Regardless of their position, the Asura realm is constantly engaged in some kind of competition, aggression, or struggle. The psychological state associated with the Asura realm is one where desire is compounding and will never be fulfilled due to the inherent root of jealousy. These beings must learn the equality of all through their addictions.

Manuṣyagati - Human Realm

Depending on the interpretation we subscribe to, this may be the realm where we reside. The Buddha of the Manuṣya realm is the revered Śākyamuni. This realm is characterized by purpose, aspiration, and possibilities. According to the Buddha, the Manuṣya realm is the most favorable realm to be born into, as it provides the best opportunity for realization and liberation.

It is important to note that the Manuṣya realm is not superior to the Tiryagyoni or any other realm. However, there are certain benefits to being in this realm, including the gift of play and creativity. When a being is focused solely on survival, “there is a paucity of play, of creativity, of curiosity, and of spiritual transcendence.”

Tiryagyonigati - Animal Realm

The Tiryagyoni realm is characterized by instincts, survival, and self-preservation, and is guided by the Buddha Stīrasiṃha. This is the first of the three realms where suffering exceeds happiness, a reality evident in our society today. Many animals suffer cruelty at the hands of humans, whether through consumption or abuse. The fortunate few may live relatively pain-free lives, yet even they are driven by instincts for survival and self-preservation.

Depending on how we interpret this realm, we can also apply these Tiryagyoni characteristics to human lives. "Pursuing animal-like desires such as eating, sleeping, and sexual gratification, without striving to cultivate one’s mind, may lead to this unfortunate rebirth."

Pretagati - Hungry Ghost Realm

Neediness, addictions, and compulsions characterize the realm of Pretas. Guided by the Buddha Jvalamukha, beings enter this realm due to their excessive cravings and attachments. One psychological interpretation posits that individuals struggling with addiction, alcoholism, eating disorders, or other compulsive behaviors exist in Pretagati.

Depictions of Pretas describe them with small, slit mouths and distended bellies. Often depicted with their necks tied in a knot, even if food or drink were available, they cannot be satiated, with some texts even suggesting that they can only consume incense smoke. Their suffering is said to far exceed that experienced in the Tiryagyonigati realm. There are some Buddhist traditions in Asia that care for these beings, leaving food and drinks out for them on ritual days each year.

Narakagati - Hell Dweller Realm

The Naraka realm, overseen by the Buddha Yama Dharmarāja, stands as the lowest of the realms, marked by agony, terror, and despair. Attachments to suffering and victimization, whether conscious or not, can lead one into Narakagati. Despite its horrific descriptions and depictions - extreme heat, cold, and visions of torture, boiling, and mutilation - these serve more as reflections of one's actions rather than eternal punishments, contrasting with the eternal hell of Christianity.

Interpreting the Six Realms

Among the various branches of Buddhism, there exist diverse theories on interpreting the Six Realms of Saṃsāra. In Theravāda Buddhism, the six realms are understood as a personal journey and a lesson in achieving liberation through the eradication of saṃskāras. These realms are often seen as psychological states that individuals navigate based on their actions, underscoring personal responsibility in the cycle of rebirth.

Mahāyāna traditions, like Zen and Tibetan Buddhism, present a wide spectrum of interpretations. Zen Buddhism tends to emphasize the six realms as symbolic states of mind that practitioners can work through and transcend. These states are fluid and can change dynamically, even within the span of a day.

Tibetan Buddhism incorporates elaborate rituals aimed at aiding practitioners in achieving positive rebirths. Practices such as meditation on the realms and teachings on the Bardo (intermediate state) hold significant importance, viewing the realms as transformative stages on the path to enlightenment.

Psychological Interpretation

This approach interprets the six realms as symbolic representations of various psychological states experienced by different types of humans. Each realm symbolically mirrors aspects of the human psyche. For example, the psychological interpretation of the Deva realm includes individuals who appear to have exceptional fortune in life. They experience ecstasy, beauty, and security, affording them the opportunity to indulge in pleasures.

However, a challenging aspect of this theory arises when considering the opposite end of saṃsāra, represented by the Naraka realm. According to the psychological interpretation, individuals who endure suffering from birth to death would be categorized in the Naraka realm. While this perspective offers a valid theoretical framework, it seems to imply that some humans are "inferior" or justify suffering as a consequence of past karmas.

Consciousness Interpretation

Similar to the psychological perspective, the consciousness interpretation places humans at the center. Here, individuals may fluidly move through different realms, potentially even within a single day. For instance, someone experiencing depression could be seen as dwelling in the Naraka realm of consciousness. This interpretation suggests that we all traverse these realms throughout our lives, influenced by how we choose to engage with karma, wisdom, and moral engagement. Naturally, our engagement in life may lead us to spend more time in certain realms than others, with the most desirable being the Manuṣyagati, offering optimal conditions for enlightenment.

Reflecting on this interpretation, one may ask, "How much time do I spend in each realm throughout the week?" You may recognize yourself exhibiting animalistic qualities in routine tasks like housekeeping or driving, where actions feel automatic and lack creativity. There may be periods of depression akin to the Naraka realm, or moments of bliss resembling the Deva realm where everything seems perfect. Reflecting on these fluctuations can deepen our understanding of how our daily experiences mirror the realms of saṃsāra.

Transmigration Interpretation

Similar to the psychological perspective, this interpretation suggests that individuals occupy different realms over successive lifetimes, shaped by their accumulated saṃskāras. However, unlike the psychological theory, this view includes the potential for rebirth not only as a human but also as an animal or another type of spirit. Some researchers, such as Ralph Metzner, propose a theory that the six realms could represent a wholly metaphysical experience, where humans inhabit the human world, animals reside in the animal world, and the remaining realms are inhabited by non-human, non-animal beings within their respective realms. This perspective underscores the continuity of consciousness and the cyclic nature of rebirth influenced by karmic conditions.

Approaching any realm with a theory of transmigration prompts us to identify and address the interplay of the three root delusions - Avidya, Rāga, and Dveṣa - in our lives during this lifetime. Through such introspection and cultivation, we strive toward attaining Moksha or, more realistically, achieving a more favorable rebirth in subsequent lives.

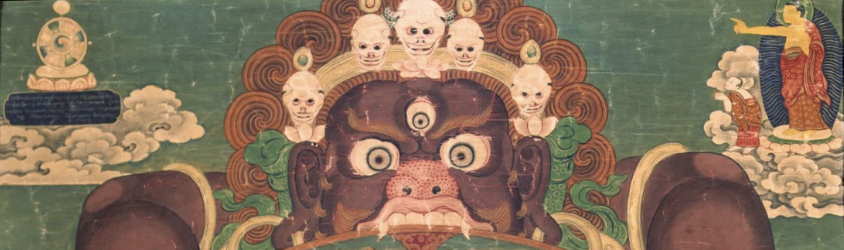

Figure 1. Detail of Wheel of Existence; Rubin Museum of Art

Bhavacakra - Art of The Six Realms

All of these theories, interpretations, and structures of consciousness and reality come together beautifully in the wheel of life mandalas, also known as bhavacakra. As seen in the image above, the demonic figure encompassing the realms is thought to be Yama, God of Death, wrapped in his tiger skins and adorned with the necklace of skulls.

Figure 2. Detail of Wheel of Existence; Rubin Museum of Art

In the central most circle, we observe a snake, a rooster, and a pig, symbolizing the three root delusions: Rāga (attachment), Dveṣa (aversion), and Avidya (ignorance), respectively. Surrounding this circle, there is a depiction illustrating the interplay between karma and saṃsāra, with figures ascending the realms on the left-hand side and descending on the right-hand side.

Figure 3. Detail of the Wheel of Existence; Rubin Museum of Art

In our next circle, we see detail of each of the six realms, with special attention to the realm of the Devas and Asuras, who in this depiction are sharing a realm. “It is no accident that a circle is used to lay out the Six Paths of rebirth. Arranging the six forms of life within a wheel relativizes the distinctions between them. The circular design suggests that gods and other inhabitants of the top part of the wheel are no different from those who suffer at the bottom”.

Figure 4. Detail of the Wheel of Existence; Rubin Museum of Art

The outermost circle is our twelve links of dependent origination - sexual intercourse (conception), a woman birthing (creating), a corpse being carried (dying), a blind person walking (blindness), a potter shaping a vessel (karmic activity), a monkey grasping (conceptual thinking), two men in a boat (words), a house with 6 windows (sense perception), lovers kissing (attraction), an arrow piercing an eye (judgment), drinkers being served (satisfied thirst), and a man picking fruit (desire).

As promised, there is the opportunity for liberation, and this is artistically depicted in the upper right and left hand corners of these bhavacakras.

Figure 5. Detail of the Wheel of Existence; Rubin Museum of Art

In this depiction, as in many others, we observe the yellow-skinned Buddha in the upper right-hand corner, positioned outside the circle of saṃsāra, pointing. Depending on the artist, this Buddha sometimes points at a moon or, as shown here, at another wheel, symbolizing liberation. The connection between each of the parts of this mandala is intricate and displays the absolute interconnectedness of this concept of rebirth within cyclic existence.

Conclusion

The six realms of saṃsāra in Buddhist cosmology offer a profound framework for understanding the nature of existence and consciousness. These realms encompass a spectrum of experiences, from the celestial realms of Devagati to the agonies of Narakagati, each reflecting different states of mind shaped by karma. They serve as metaphors illustrating the consequences of actions and the cyclic nature of suffering rooted in ignorance, attachment, and aversion.

Throughout this exploration, we have examined various philosophical interpretations of the Six Realms, explored the role of karma in rebirth, and uncovered their symbolic meanings. The mandala art of the wheel of life integrates these concepts, providing a unified understanding of the interconnectedness of existence and consciousness.

Studying these realms offers profound insights into human nature and the potential for both suffering and liberation. It prompts reflection on how to transcend the cycle of saṃsāra through wisdom, ethical conduct, and mental discipline. Embracing this understanding encourages a mindful approach to life, fostering compassion and wisdom as we navigate the path toward spiritual growth and liberation.

Sources Cited

Chapple, Chris. Karma and Creativity. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1986.

Metzner, Ralph. "The Buddhist Six-Worlds Model of Consciousness and Reality." The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 28, no. 2 (1996): 155-166

Sakai, Nanako. "Ancestors are the Storytellers: The Realm of the Hungry Ghost and Hell in Buddhism." Religious Education 117, no. 5 (2022): 414-425. Published by Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344087.2022.2149133

Stephen J. Laumakis, "Kamma, Samsara, and Rebirth." In An Introduction to Buddhist Philosophy, 83-104. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511800818.009.

Teiser, Stephen. Reinventing the Wheel: Paintings of Rebirth in Medieval Buddhist Temples. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

Verchery, Lina. "Both Like and Unlike: Rebirth, Olfaction, and the Transspecies Imagination in Modern Chinese Buddhism." Religions 10, no. 6 (2019): 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10060364.

Artwork

Eric Huntington, “Wheel of Existence: A Visual Explanation of Buddhist Cosmology,” Project Himalayan Art, Rubin Museum of Art, 2023, http://rubinmuseum.org/projecthimalayanart/essays/wheel-of-existence